A white American and a Nigerian read Jean Toomer’s Cane

(Updated December 2020 and March 2025)

I picked up Jean Toomer’s Cane (1923) to listen in on words from an old rural black Georgia that was still touched by slavery. What I found was an appreciation for black beauty.

The Norton Critical Reader edited by Rudolph P. Byrd and Henry Louis Gates Jr. informed me that Toomer was not an insider to old rural black Georgia culture. A mixed-race middle-class Washingtonian, Toomer came to Georgia in 1922 for only three months to serve as acting principal of Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute, a black institution in the small town of Sparta, about 80 miles southeast of Atlanta. According to Toomer quoted there, “I had always wanted to see the heart of the South. Here was my chance.” Toomer had ancestors from Georgia on both sides of his family. In Sparta Toomer encountered a black folk culture of folksongs and spirituals for the first time, and he tried to capture it in writing before it disappeared.

This fragmented work moves in three parts from vignettes about the rural South to short stories about the urban north, to a play in prose set again in the rural South. It combines poetry, prose, and drama. Characters are black, white, and mixed race. It seems that Toomer struggled with his racial identity; he could pass as white but was repeatedly classified as black and sent to segregated black schools. His masterpiece Cane was became a classic of the Harlem Renaissance, but Toomer himself subsequently denied his black race and drifted away from writing into obscurity.

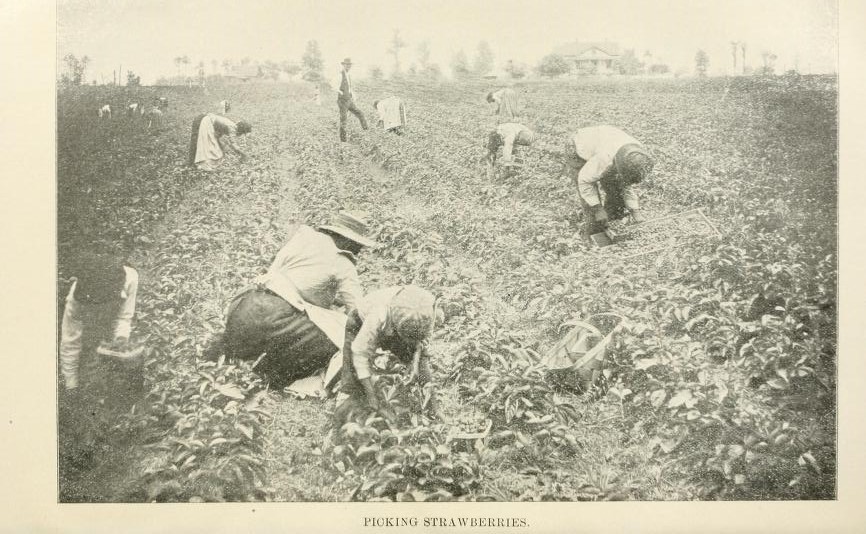

The title of the work suggests several things — sugar cane, caning, Cain, cane weaving — which may be found in the book. I learned that sugar cane is among the crops grown around Sparta (even to this day). Cane brakes figure frequently in Cane as areas of meeting, and cane stalks, cane leaves and cane syrup appear as sources of sweetness. Cane imagery also finds its way into the urban stories, as though an ancestral land is calling. Other crops grown in the region included cotton, corn, wheat, potatoes, beans, peaches, and strawberries.

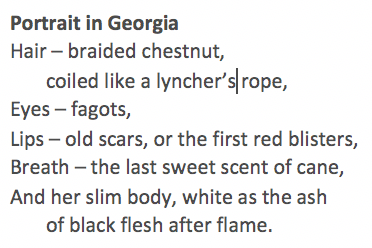

Cane was written during Jim Crow, and Toomer’s poetic portrait of a black woman seems to highlight pain:

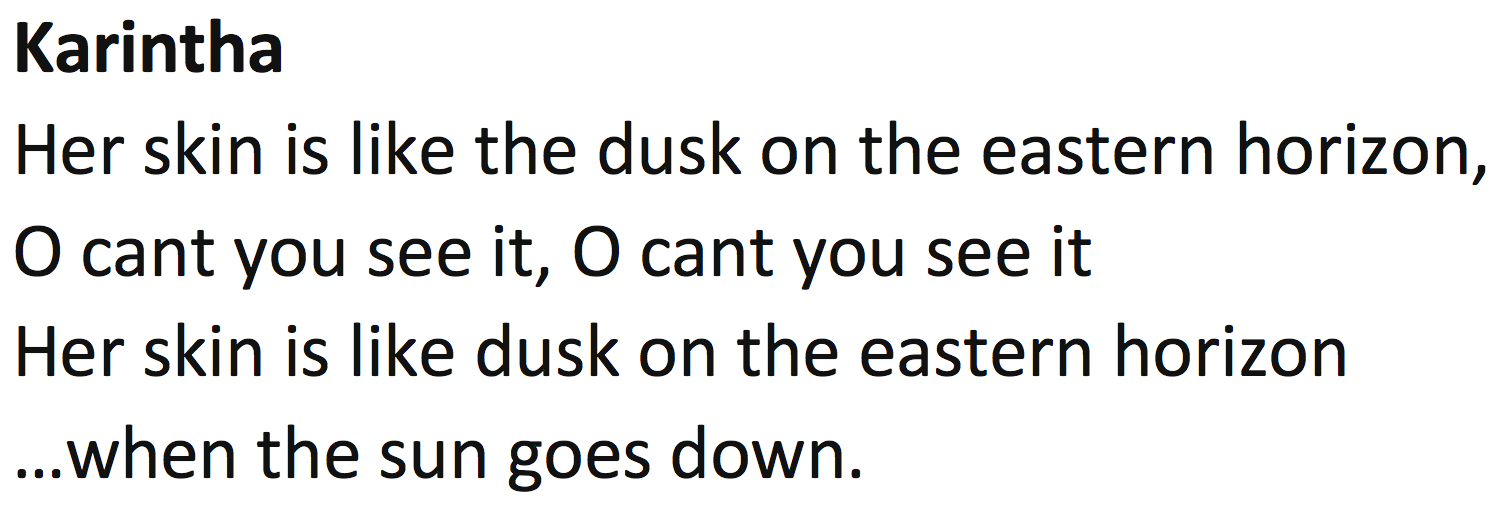

The first third of Cane is dense with the beauty and vitality of women, sundown, smoke rising, moons, song, pine and resin, and the red clay of Georgia. Here Toomer captures in jazz beats the color of a character’s skin:

And there are many passages singing such beauty. This celebration of black beauty on its own terms must have been bold in 1923.

And it may still be today. Ifemelu, the Nigerian-born main character of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel Americanah (2013), was also reading Jean Toomer’s Cane as she sat in an African hair salon in Trenton, NJ, getting her hair braided one last time for her journey home after living for 13 years in the US.

Ifemelu is a young woman of a generation of Nigerians that sought education abroad in the United States or United Kingdom. Her only experience of the US before moving here was with wealthier Nigerians who had visited, including her aunt, the kept-woman of a Nigerian general, who came to Atlanta to have her baby, presumably because the hospitals were better.

In coming to the US to study and work, Ifemelu says she encounters race for the first time and struggles to interpret what it means. The distinction between African and African-American is collapsed into “black” and she is for the first time juxtaposed against something called “white.” In her effort to understand race, Ifemelu starts a blog called “Raceteenth or Various Observations about American Blacks (those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black.” When Ifemelu tries to get a job, her recruiter advises her to try to blend in better with white beauty norms: “lose the braids and straighten your hair.” When she gets her hair braided and reads Cane she seems to be reclaiming her own natural beauty.

Last month at a meeting in Chapel Hill, NC, I met Oluwamuyiwa Winifred (“Winnie”) Adebayo, Assistant Professor of Nursing at Penn State who is Nigerian born and had a lifestyle blog, and we connected over Americanah. Winnie agreed with Ifemelu’s comment about discovering race in the United States, saying, “In Nigeria we have issues but we never think of skin color.” Winnie especially identified with Ifemelu’s “hair journey.” She described some of the issues with black hair: Water shrinks and tightens it and so is a threat to styled hair; she has to plan around hair washing, rain, and swimming. Relaxers soften black hair and make it more manageable but with chemicals that may be hazardous. Like Ifemelu, Winnie eventually her way to the Natural Hair Movement and renounced relaxers. The decision embraces “hair as it grows out of my head,” she said.

Here Winnie reads Ifemelu’s words (pp 365-6) on how black women and their beauty issues are left out of American fashion magazines:

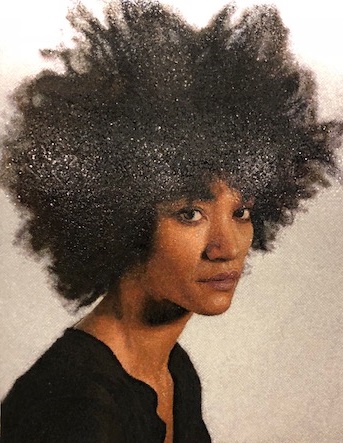

As someone living within white American beauty norms and taking them for granted, I was moved by this passage. It may be that images of black beauty and natural black hair are starting to enter public spaces to stay. Take Chuck Close’s mosaic Sienna with her Afro in the subway line that opened in Manhattan in 2017:

So why is Ifemelu reading Cane? It is left to the reader to decide. Ifemelu has just broken up with African-American professor boyfriend Blaine, who called the book “precious” and steered her away from it; she’s rebelling against his comments and now thinks she’ll like it. As the story weaves back in time and returns to the hair salon, Ifemelu returns to Cane and suddenly wants to postpone her decision to give up on the US and move home, thinking she’s being hasty. A white customer comes into the salon wanting braids, and soon after offers up the opinion that it is wonderful that the US gives Africans a chance for a better life. She then reaches out to Ifemelu, trying to engage her over her book. In her state of mind Ifemelu doesn’t want to engage. The woman persists and the tension between the two women mounts. When the conversation ends Ifemelu reflects at length on the complexities of her experiences with a white ex-boyfriend and their attempts to understand each other. Even – or especially – in a beauty salon it is impossible to get away from race.

Maybe Ifemelu picked up Cane, like me, to try to touch a past that influenced today’s black-white relations in the US. In a sense she gives up and goes home to her own people. Ironically, when she gets there she’s teased for having turned into an Americanah, someone with American ways and pretensions that are foreign to Nigerians – having been changed by her experience. Those conversations were in her.

Addendum: On February 21, 2019, the New York Times published “City bans discrimination based on hair” describing new guidelines released by the New York City Commission on Human Rights establishing the right to maintain “natural hair, treated or untreated hairstyles such as locs, cornrows, twists, braids, Bantu knots, fades, Afros, and/or the right to keep hair in an uncut or untrimmed state.” The guidelines follow the highly publicized incident in December involving New Jersey high school wrestler Andrew Johnson who had his dreadlocks forcibly cut before a match.

Thank you Anna for guiding me through these two fascinating books. So much to think about particularly in these days and times.

LikeLike

Challenging times call for mental and emotional action…

LikeLike