Ian McEwan joins a debate about the novel’s impact today

delivering News to You: Literature Isn’t Dead

A few months ago, a friend texted me News to You: Literature Isn’t Dead, Ann Patchett’s impassioned defense of literary fiction’s centrality to American culture today. The novelist, who runs the bookstore Parnassus in Nashville, Tennessee, was responding to an op-ed in the New York Times by the conservative political commentator David Brooks called When Novels Mattered about a period in American history ending in the 1980s when, he claims, literary authors were audacious, big in scope, unconstrained by political correctness and liberal conformity, and therefore actually mattered to the culture – unlike now.

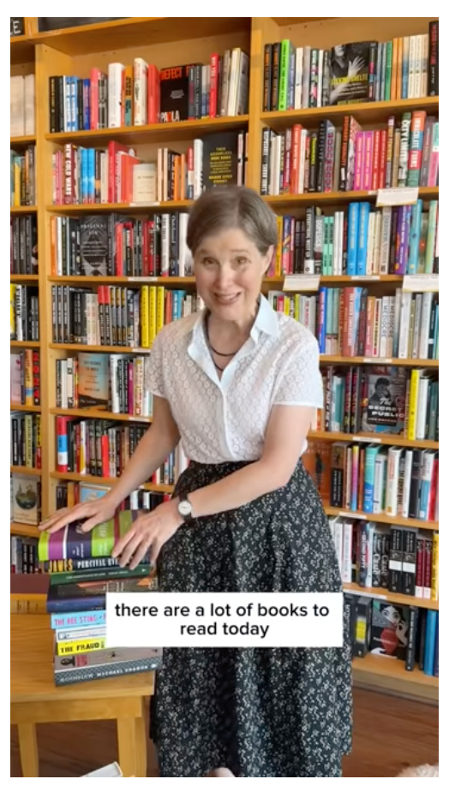

Patchett hit back with 15 titles that she considers audacious and significant to culture today. They are (with my annotations added on when they were published and when they were set):

- The Night Watchman (2021) by American author Louise Erdrich – set in the 1950s

- James (2024) by American author Percival Everett – set in the 1840s

- Inheritance of Loss (2006) by Indian author Kiran Desai – set in India in the 1980s

- The Overstory (2018) by American author Richard Powers – set from the 1880s to the present

- Playground (2024) by American author Richard Powers – set now and in near future

- Native Speaker (1995) by American author Chang-Rae Lee – set during the 1990s

- The Bee Sting (2023) by Irish author Paul Murray – set now

- Demon Copperhead (2022) by American author Barbara Kingsolver – set in the 1990s

- The Fraud (2023) by British author Zadie Smith – set in the late 1800s

- What is the What (2006) by American author Dave Eggers (in conjunction with a lost boy of Sudan Valentino Achek Deng) – set in the early 2000s

- Moonglow (2016) by American author Michael Chabon – set in the 1980s and before

- Harlem Shuffle (2021) by American author Colson Whitehead – set in the 1950s and 1960s

- Crook Manifesto (2023) by American author Colson Whitehead – set in 1970s

- The Goldfinch (2013) by American author Donna Tartt – set in the early 2000s

- Lush Life (2008) by American author Richard Price – set in the early 2000s

I was interested in when Patchett’s recommended books were set because, although Brooks is very unclear, I infer that he is looking for social realist fiction about the here and now representing a swathe of social classes and races, with explosive conflict and perhaps satire – along the lines of Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) which he admires. According to those criteria, only three of Patchett’s recommendations would meet that mark: the Jim Powers novels (Overstory and Playground) and Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting.

David Brook’s own list of works that mattered in the past is undisciplined and sprawling, conflating a number of criteria:

- 1) bestseller status (who appeared on Publishers Weekly’s annual list of top 10 bestsellers in the US as an indicator of impact – e.g., Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov in 1958, Dr. Zhivago by Boris Pasternak in 1969, Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth in 1969, and Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow in 1975).

- 2) celebrity status (who appeared in the tabloids – e.g., Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, Truman Capote)

- 3) era and geography (who was from the Anglosphere anytime from the 18th through the 20th century – e.g., F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, George Eliot, Jane Austen, or David Foster Wallace), and

- 4) audacity (who bucks tradition – e.g., The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon, and Humboldt’s Gift by Saul Bellow, as well as Edith Wharton, Mark Twain and James Baldwin).

I fact-checked one of Brooks’s claims, that not a single work of literary fiction has appeared on the Publishers Weekly’s annual list of top 10 bestsellers in the US since The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen in 2001, and Brooks came up short. In fact, another work by Jonathan Franzen, Freedom, appeared on that list in 2010. If Wikipedia’s entry on the subject is accurate, since 2001 the following literary works have also appeared on the Publishers Weekly annual list:

- 2002 and 2003: The Lovely Bones (2002) by American author Alice Sebold (who, by the way, achieved much lurid celebrity notoriety on the scale of Normal Mailer) – set in the 1970s

- 2005: The Mermaid Chair (2005) by American author Sue Monk Kidd – set in late 1980s

- 2007: A Thousand Splendid Suns (2007) by Afghan-American author Khaled Hosseini – set in 1960s to early 2000s Afghanistan

- 2008: The Story of Edgar Sawtelle by American author David Wroblewski – set in the 1970s

- 2010: Freedom (2010) by American author Jonathan Franzen – set in 1980s to present

- 2013: The Great Gatsby (2025) by the late American author F. Scott Fitzgerald – set in 1920s

- 2015: Go Set a Watchman (2015) by the late American author Harper Lee – set in the 1930s

- 2015: To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) by tbe late American author Harper Lee – set in the 1950s

- 2016: All the Light We Cannot See (2016) by American author Anthony Doerr – set in 1940s France

- 2020: Little Fires Everywhere (2017) by American author Celeste Ng – set in 1990s

- 2021: The Song of Achilles by American author Madeline Miller – set in ancient times during the Trojan War

These oversights might be explained by Brooks’ dismissing the classics as unimportant reruns as well as ignoring any work that is even slightly historical. However, some of the novels on his own lists are backward-facing too. I think the reason Brooks misses Jonathan Franzen’s second best selling book in 2010 is because he is not reading the lists himself; he is, it seems, lazy.

Many people I know believe that the times we are living in can best be understood through consideration of the past, historical fiction. Though this Lit Alive! blog is about literary sightings that come at me, my favorite literary genre is, in fact, the opposite of historical fiction — I prefer novels set in the near future or with alternative presents that show us where our culture might be headed. There is nothing timid or conformist about considering the effects of climate change and technology, and my list of big audacious works that have had impact would include at least the following:

- The Circle (2013) by American author Dave Eggers – set in the unspecified near future

- The Children’s Bible (2020) by American author Lydia Millet – set in the present or near future

- Klara and the Sun (2021) by British author Kazuo Ishiguro – set in the unspecified future

- Prophet Song (2023) by Irish author Paul Lynch – set in an alternative Ireland today or in the near future

- What We Can Know (2025) by British author Ian McEwan – set in 2120.

Ian McEwan, whose futuristic literary thriller of sorts What We Can Know just came out in September, seems to respond directly to Brooks through the literary mouthpieces that inhabit the book. McEwan considers the future legacy of our current information age and directly comments on the controversy of how novels matter today.

In this novel, literary scholar Tom Metcalfe is searching for a lost unpublished poem (“corona for Vivien”) written by a famous poet to his wife that has achieved mythic status in the 100-some years since its reading at a party in 2014. In the 22nd century, everything once in the cloud is now data managed by the Nigerians and freely available to everyone; the US is mostly out of bounds because it is controlled by warlords; use of the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford requires boat trips because Britain is now an archipelago; and AI is now injected in dosages. In combing through the archives from our present era, Metcalfe constructs the biography of the poem’s creation only to later learn that based on this evidence he is wrong about almost everything.

On the way to the finale, the scholar Vivien Blundy, wife of the famous poet, decides to leave her academic humanities position, lamenting “our old centrality to the culture gone.” However, Tom describes the historic period of “The Derangement” (2015-2030), from his 22nd century vantage point this way:

The times were copious, like rivers in spate. Its teeming hoards of novelists, poets and dramatists formed a giant army massed against its readers, who were never quite sure of what was good. So the arguments were insecure and loud, and that was fine, a democracy of contesting tastes, a chaos of unconformity.

In contrast to our times, the characters live in the isolation of the little islands which kill diversity and in fact everyone in this era has become the same shade of light brown. Tom comes to agree with his colleague Rose that “the Derangement could not have been addressed by fictional realism. It was inadequate to the scale of the problem.” It seems that McEwan disagrees with Brooks that we especially need social realist novels.

McEwan’s voice, through his protagonist, suggests that our times are still ok in terms of literary output, and our problem is not that we have a great quashed conformity of voices from writers going through MFA programs in the liberal university system, as Brooks asserts. Instead, a great many voices that were formally suppressed have suddenly arrived through opened gates all at the same time and now they struggle to be heard – and us readers struggle to keep up. The quantity and lack of focus may be challenging, indeed off-putting, to would-be readers. It’s understandable.

I’m not sure they’re reading literary fiction.

To state the obvious, writers today are also competing within an attention economy that has become hugely fragmented. Brooks dismisses the advent of the Internet as the reason for the decline in literary reading because he says the decline began in the 1980s. I have not yet checked those facts (and there is a lot in the op-ed that needs fact-checking or triangulation). Regardless, “the Internet” is an oversimplification of the many technological platforms that have fragmented our attention since the 1980s, including the mobile phone and its camera, streaming video and music, podcasts, audio books, social media, and new kinds of texts such as manga and video games as well as texts and tweets. In this context, the force of any one stream, such as literary novels, is diluted.

Incidentally, Ian McEwan made a late-night comedy circuit mention – does that celebrity status mean his novel matters?

Let me give the last word to Ann Patchett who got us here. She suggests that writers today don’t want to be Taylor Swifts, and that there is plenty of audacity around (consider Percival Everett having the audacity to rewrite Huckleberry Finn from the point of view of the slave “Jim” – now restored to “James”). The only way to truly make room for long-form text is to make the radical decision to get offline, embrace silence, and give time and attention to reading. Very hard to do that if you are trying to be a media celebrity yourself.

See more at lit-alive.com.