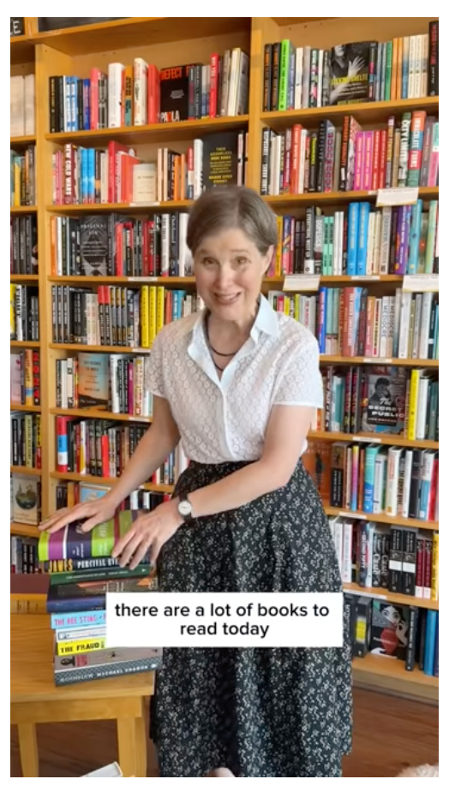

Storm Murray cosplays Zanka from Gachiakuta at Anime Weekend Atlanta

A few years back I asked a doctoral student at Georgia State University to help me set up my English course on the learning management system there. Her name was Storm Murray and incidentally, her own course landing page was the most beautiful I’d ever seen. In gratitude for the help, another instructor and I took her to lunch. What Storm talked about was her love of cosplay, or the art of dressing up as characters from manga (Japanese graphic novels) and anime (Japanese animated film), either within an online community or at an in-person “con” or themed fandom conference. It was the first time I’d encountered someone who brought books to life through cosplay.

In November Storm and I met up at The Rookery in Macon, Georgia, where she lives and currently teaches English composition at Wesleyan College. She told me about her dissertation, cosplay, the overlap between the two, and her latest cosplay foray at the Anime Weekend Atlanta (AWA).

As an academic who has insider cultural knowledge (Henry Jenkins’ “aca-fan” perspective), Storm is tracing the history of fandom to argue that “English scholars need to recognize and reconceptualize what fandom is because we have historically looked down on these communities as unworthy of scholarly concern and because of that have missed valuable lessons that these communities can teach us as instructors of writing.” Discourse communities form around fandom, she says, and members become highly literate in their discourses, making arguments and using evidence, for example, in ways that can transfer to the college classroom. From the 1880s followers of Sherlock Holmes and Jane Austen “Janeites”, to the birth of modern fandom with Star Trek in the 1960s, to physical zine exchange, Usenet bulletin boards, Internet archives, and social media, these communities demonstrate resilience over political and technological change and highlight opportunities for knowledge transfer.

Upcoming in December was Anime Weekend Atlanta where Storm was planning to cosplay several characters, including Zanka from Kei Urana’s manga Gachiakuta. After our meeting, I read the first of 17 volumes of Gachiakuta (2022, translated into English by Jennifer Ward in 2024) and watched a few episodes of the anime on the anime streaming service Crunchyroll, where you can sign up for a 7-day free trial.

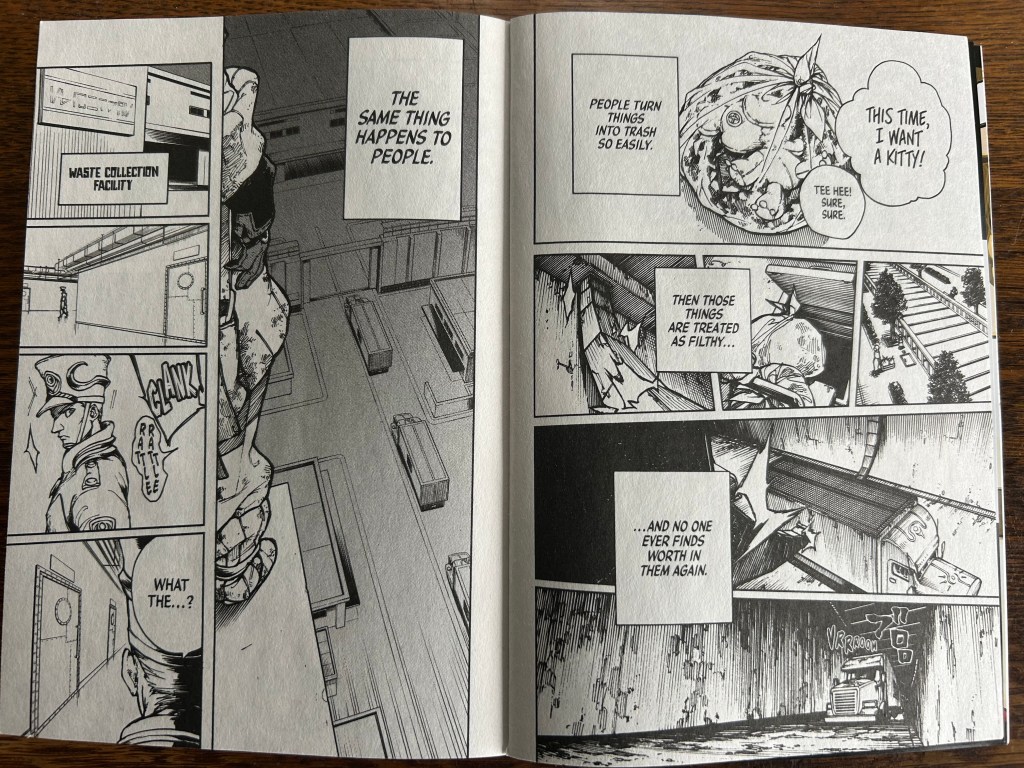

In Gachiakuta, the 15-year-old hero Rudo lives on the tribesfolk’s side of a wall in the segregated world known as “The Sphere.” He rescues objects thrown in the trash by those on the privileged side of the wall. This practice is considered a transgression in this overly hygienic homogenous town; Rudo is chased and shot for saving a slightly ripped teddy bear, which he gives to a girl Chiwa. Ultimately all trash is thrown off the Sphere into a world below known as “The Ground” or “The Pit,” including people who are considered trash. Soon Rudo is falsely accused of murder and thrown into The Pit. There he encounters a whole other world of toxic air requiring gas masks and enormous “pseudo-living things” or trash monsters that have to constantly be fought by The Cleaners. The Cleaners recruit Rudo to their team because he is a Giver, someone who through love and care imbues a particular object with soul that can be harnessed by them as weapons (“vital instruments”) to decimate evil.

After the conference, Storm and I talked again. Storm sees Gachiakuta as cutting edge:

I think it’s a really great reflection of right now, where the wealthy can throw away without even thinking about it. When you can’t do that, things come to mean more to you than perhaps they would otherwise because that’s the only thing you have. The vital instrument, you come to find out, is not just the thing you had with you the longest, it’s the thing that you’ve poured yourself into and is representative of you and your values. So you think about a pair of scissors, why would that be a vital instrument? Or Enjin’s umbrella, why would that be a vital instrument? But it’s because, for whatever reason, it’s the thing that person sees as a part of themselves, and that is where it gets its power, the meaning that’s placed onto it, not because it is just an umbrella that is a useful tool, it’s the meaning that gives the thing value, and you can’t throw that away.

Another reason that Gachiakuta “blew up a little bit” in popularity last year, she says, is because unlike most traditional manga and anime it features different races and ethnicities. Semiu Grier, the administrative assistant of The Cleaners, whose glasses are her vital instrument, is Black, as is the leader of the Cleaners organization. The one Japanese character, the author has stated, is Zanka, yet he too is played in the English dubbing of the anime by the Black voice actor Corey Wilder. Storm notes that anime and manga fandom comprise “a very white-centric space … just like the industry behind anime and manga in the US, and so Gachiakuta is a really refreshing change from that.”

In addition to pointing out class callousness and expanding representation, Gachiakuta also critiques consumer culture in general:

To be involved in society there’s a flagging technique, where if you have a Labubu you’re in on the trend, you know about it. Or you have a Stanley Cup, you’re up to date on the cultural moment. It’s true about fashion, it’s true about accessories, it’s the kind of clothes you’re wearing, and it’s all because of social media, especially TikTok, I think…. Now I think there’s been pushback because it promotes spending money, and people are realizing that we can’t afford it anymore, which is why I think there’s been such a resurgence in (I can at least attest to my own social media algorithm) people who are really getting into gardening again to grow their own food, getting into sewing so that they can make their own clothing, or thrifting, and stuff like that. So the story of Gachiakuta is really tapping into that, seeing the value of the things that we have and not just what the culture attributes their value to be.

These trends apply to the world of cosplay itself, where fans try to stay up with the most current shows and cosplay them; there is starting to be more awareness of “fast-fashion” waste and the need to slow down consumption and encourage an aftermarket for cosplay costume resell, according to Storm.

Gachiakuta Book 1 ends when Rudo meets his assigned trainer, Zanka. Why did Storm choose Zanka to cosplay and not, say, Rudo, Enjin, Semiu Grier, Rio, or one of the other Cleaners? She says she was intrigued by Zanka’s nonchalant facade, his rigidity about cleanliness, among other things, and his deep caring underneath it all. She also liked his recognition that he isn’t a genius and his steadfast work ethic to be better than a genius. Finally, Storm said, she can’t resist “a big prop”: “The first time that Zanka activated his Assistaff, which is the name of the weapon, I was like ‘Oh my God, I gotta make it, it’s so cool,’ it has the glowing elements to it and stuff, so I was like ‘I have to make it.’ I put LEDs in it; it did light up.”

Note the different interpretations of the Assistaff (courtesy of Brian Henderson)

While the prop creation was a big motivator for Storm, she bought the costume online from the Chinese website Holoun. Zanka sells for about $150, not including boots which Storm already had, the wig which she bought separately and styled herself, and the Assistaff, which she made. China is the epicenter of fandom manufacturing, according to Storm, with nothing equivalent in the US outside of private commissions. I asked about tariffs and Storm mentioned that the announcement of tariffs was “a really big scary thing” in the cosplay world and that prices have jumped, making people scale back their hobby. On top of buying the costume, registration for the conference is about $100, and Storm and her husband rented a hotel room for the duration of the 3-day conference. The online schedule made the event look like a 24/7 slumber party to me, with watch parties, panels discussions, events with Who’s Who of AWA, games, concerts and parties all night long in the World Congress Center, so to get your money’s worth you’d want to stay close by.

Storm herself was almost destined to get deeply involved with fandom. She is named after a character in The X-Men, as is her younger brother Phoenix; while their younger sister is named Ryder after a character in Ghost Rider. Their Dad collected comics, their grandmother Gone with the Wind memorabilia, and their mother is a football fan.

But what does Storm get out of cosplay?

Community is a big one. I really like when I’m cosplaying a character and somebody is like, ‘Oh my God, can I take a picture of you?’ or ‘Oh my God, are you so and so? I love that show,’ and then we get to talk about it. It’s just a really wholesome moment of shared passion and love and a moment of community. Another piece is I really like that I get to stretch a lot of muscles in that cosplay requires so many skills; instead of being a master of one I’m a jack of all trades. So I get to play with hairstyling, I get to play with building, crafts, painting, I mean every kind of craft material you can imagine … and I have skills that I never would have thought I would learn because of this hobby. And then I just really love being these characters. While I’m not playing them at full send, I do get to embody them, I feel pretty powerful in this outfit or I feel a little more confident in my body in this outfit because this character is very pretty and every time I pass somebody they’re like ‘Oh my God, I want to take a picture of you, you look so pretty,’ it’s nice, you know what I mean? … I really do think that me being in the anime community and being in the cosplay community was a big shaper of my perception of gender and sexuality and things like that because I went to a very small conservative Christian white private school. I was not at all exposed to that in any way shape or form, except through my online channels and media but I’ve been cosplaying and dressing as a dude since I was 17.

Storm’s manga and anime choice took me back to Tokyo in the early 1990s when I taught English there. Having spent time in the famously and elaborately polite Japanese culture, I was surprised by the foul language and violence of this manga, but it goes with the genre, a shonen, written to appeal to boys from around age 11 to 16. Rudo is particularly foul-mouthed but he has reason to be, and it is clear to me that he is a surly protagonist with a heart of gold.

The manga also reminded me of the tremendous ironies and confusions I experienced as an outsider to the Japanese culture decades ago. I knew about the sanctity of cleanliness in Japanese culture within Shinto and Buddhism, and I remember the scalding-hot sento (public baths) tucked into every little neighborhood. But how strange it is also to remember the way we gaijin foraged in the gomi (trash) near apartment buildings after Christmas and New Year’s holidays for the pristine brand-new objects and, even better, that famously sumptuous, gorgeous, elaborate packaging (boxes, crates, baskets, paper wraps, etc.) left there; this practice does appear to be illegal now. Packaging of any kind was always stunning and so were the umbrellas (like Enjin’s) that danced about above the narrow streets in the rain to avoid hitting each other. Yet I remember doing laundry in a public laundromat while a smoker sent clouds of smoke into the air and wondering, when he refused to budge, how I was going to whisk my sheets from washer to dryer and out again without getting that nightclub scent. I remember salarymen shaving on the train on their way to work and others throwing up on the sidewalk after a night’s carousing. How bizarrely delightful were the noise machines in public bathrooms to hide sounds of bodily functions. And, incidentally, I do remember the rockabilly cosplay at the Harajuku subway stop and the bar where Japanese bartenders wore dredlocks; I just didn’t know the name for it. Most deeply enduring for me now, perhaps, is the Buddhist aesthetic of art and objects as living things which decay over time, as we do, and how one shouldn’t necessarily try to preserve them because life is ephemeral and beautiful, to be savored and appreciated at all changing moments before we die.

Here are a few burning questions that make me consider continuing with Gachiakuta: Does Rudo find his father in The Pit? (That is, was Rudo’s father also falsely accused of murder and thrown over the side of The Sphere like Rudo?) Does Rudo ever make it back to The Sphere? What happens between him and Chiwa? How does Rudo use his power as a Giver? What are the trash monsters, what gives them power; is it neglect and scorn, the opposite of love and care? What, ultimately, does “gachiakuta,” which is slang for “legit trash,” refer to within the story?

See more at Lit-alive.com