Ian McEwan joins a debate about the novel’s impact today

delivering News to You: Literature Isn’t Dead

A few months ago, a friend texted me News to You: Literature Isn’t Dead, Ann Patchett’s impassioned defense of literary fiction’s centrality to American culture today. The novelist, who runs the bookstore Parnassus in Nashville, Tennessee, was responding to an op-ed in the New York Times by the conservative political commentator David Brooks called When Novels Mattered about a period in American history ending in the 1980s when, he claims, literary authors were audacious, big in scope, unconstrained by political correctness and liberal conformity, and therefore actually mattered to the culture – unlike now.

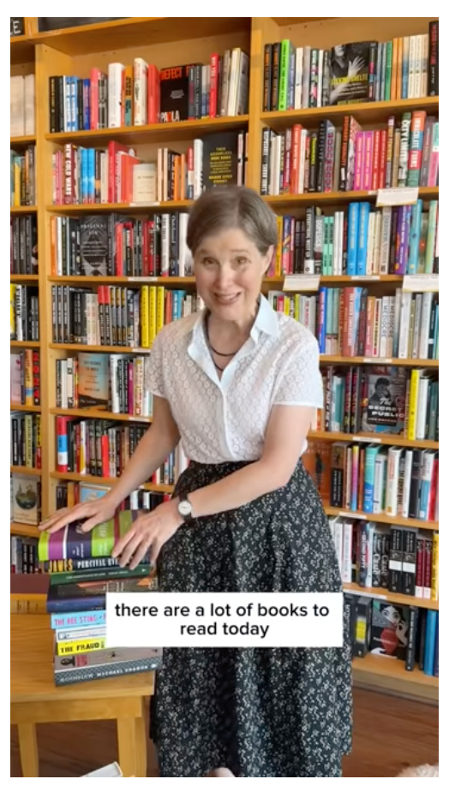

Patchett hit back with 15 titles that she considers audacious and significant to culture today. They are (with my annotations added on when they were published and when they were set):

Continue reading A Chaos of Nonconformity